Sidney M. Wolfe, a doctor turned consumer activist who battled drug companies, lobbyists and regulators during a nearly five-decade crusade against ineffective, risky and overpriced medications that made him a hero to patient advocacy groups and an implacable foe to anyone who opposed him, died Jan. 1 at his home in Washington. He was 86.

The cause was a brain tumor, said his wife, Suzanne Goldberg.

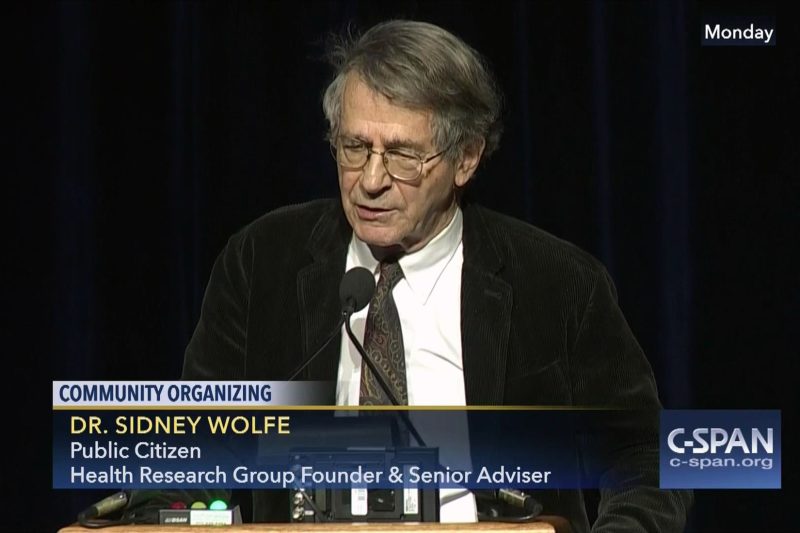

Dr. Wolfe did not practice medicine for long and instead spent most of his career with the Health Research Group, part of the Washington-based Public Citizen organization founded by consumer activist Ralph Nader.

Driven to expose drugs and medical devices that he was convinced could kill or harm patients, he searched for clues in thousands of research papers and medical journals, stacking them in fire-hazard piles around his office. Scientists at regulatory agencies, especially the Food and Drug Administration, leaked information to him, typically under cloak of anonymity. (One source called himself Dr. Doonesbury, after the comic strip that skewered politicians.)

Dr. Wolfe is “almost unique in the world of drugs,” Michael Jacobson, then the executive director of the Center for Science in the Public Interest, told the New York Times in 2005. “He spends his life systematically looking for problems, and he finds a remarkable number.”

His petitions and lawsuits helped get more than two dozen dangerous or ineffective drugs removed from the market.

The banned medicines include the diabetes drug Phenformin, which was linked to hundreds of deaths; the anti-inflammatory Vioxx, which caused serious heart damage; and the anti-diarrheal Lotronex. He also successfully petitioned federal regulators to include a warning on aspirin bottles about Reye’s syndrome, a potentially fatal condition linked to children’s use of the pain-relief drug for the flu or chickenpox.

“Sid has the capacity to put things on the FDA agenda,” Robert Young, an FDA official and rare Wolfe admirer within the agency, told the Wall Street Journal in 1985. “When [Health Research Group] files a petition, it’s looked at very carefully.”

In a statement, Nader praised Dr. Wolfe for “stressing prevention of trauma and sickness, accountability for gouging and unsafe practices by the drug companies and effective regulation by the FDA and [the Occupational Safety and Health Administration]. … Millions benefited from this work.”

Among his critics, Dr. Wolfe acquired a reputation as a regulatory Chicken Little in his early campaigns against Alka-Seltzer, cough syrup, contact lenses, food additives, toothpaste and entire professions (dentistry, psychiatry).

An official at the Pharmaceutical Manufacturers’ Association, the drug industry’s main lobbyist, told The Washington Post in 1978 that “his problem is an excess of zealotry. He tends to exploit every negative aspect of drug therapy to scare the consumer.” An FDA official once called him “adversarial, unfair and self-serving.”

These critiques were declarations of valor to Dr. Wolfe. He thought drugmakers, regulators and physician groups were too cozy with one another, leading to the approval of unsafe and ineffective treatments. He was formidable, especially when testifying to drug-approval panels or in Congress with his booming, trembling voice.

“When someone contradicts what Sid thinks is scientific truth, he goes ballistic,” Nader told the Times. “He doesn’t suffer fools gladly.”

FDA Commissioner Donald Kennedy told Time magazine in 1978, “Sometimes when I’ve been annoyed at Sid, I realized that I was really annoyed at myself for not seeing a problem to be as serious as I should have at first look. In the past, the tendency was not to question the fruits of technology.”

When Dr. Wolfe found a smoking gun in scientific papers, he often circumvented bureaucrats and went directly to agency heads to effect change, and he pestered reporters for coverage. Malcolm Gladwell, who as a Post business and science reporter in the 1980s endured many of his phone calls, anointed him “the nudge of Washington.”

“My memories of Sid is you would never know when you would get off the phone,” Gladwell said in 2022 during an episode of his podcast, “Revisionist History,” that focused on Dr. Wolfe’s early and widely ignored concerns about opioid painkillers.

“He’ll not just talk to you,” Michael Specter, another ex-Post science reporter of that era, recalled during the podcast. “Then the information starts flowing. In those days, the fax started to churn because that’s how we got stuff. I would go out to lunch, and if there was a pile of fax paper on my desk, it would be like ‘Sid struck.’”

Sidney Manuel Wolfe was born in Cleveland on June 12, 1937, and grew up in a “very liberal, progressive” household, as he once described it. His father was a workplace safety inspector for the Labor Department, and his mother taught English in public schools.

As a teenager, he had the inclinations of a Renaissance man. He joined the Atomic Science Club in high school and wrote letters to Albert Einstein. He also hung out at jazz clubs. “I was 15,” he told The Post, “and I’d sit there for six hours, listening to Brubeck, Gerry Mulligan, Chico Hamilton, Art Pepper, back when progressive jazz was happening.”

In 1959, Dr. Wolfe received a bachelor’s degree in chemical engineering from Cornell University. A summer job working with hydrofluoric acid that gave him first-degree burns convinced him not to pursue a career in chemistry. He went to medical school instead, earning his degree in 1965 at Western Reserve University (now Case Western Reserve University). He trained under pediatrician and antiwar activist Benjamin M. Spock.

To avoid fighting in the Vietnam War, Dr. Wolfe said, he joined the Public Health Service. He was active in the 1960s protest movements as a member of the Medical Committee for Human Rights, a leftist antiwar group that also battled the American Medical Association on equality issues in medical care.

After rejecting his membership in the AMA, Dr. Wolfe volunteered with groups providing medical care to antiwar demonstrators and the poor. One evening, he called a doctor friend from the National Institutes of Health to help take care of a woman associated with the Black Panthers. “He said, ‘Get your a– out of bed,” the doctor, Anthony S. Fauci, told the Journal. “That’s vintage Sid.”

In 1971, Dr. Wolfe was conducting blood research at NIH when a scientist friend at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention called him with a complaint. Federal regulators, the friend said, were refusing to recall the widely used but contaminated intravenous fluids made by Abbott Laboratories.

Hundreds of patients were sickened, and some died. Abbott said a recall would leave patients without important fluids. The government, in response, told doctors to cease using the fluids at the first sign of infection.

In a fury, Dr. Wolfe reached out to Nader, who had recently started Public Citizen. Nader suggested they write a stern letter to the FDA.

“It is a form of malpractice to wait until a patient develops evidence of a blood infection discontinuing the use of products known to have a high incidence of bacterial contaminants,” they wrote to FDA Commissioner Charles C. Edwards. “It is a cowardly repudiation of the ethic of preventive medicine.”

Dr. Wolfe and Nader also sent the letter to reporters. A few days later, the FDA recalled millions of bottles of the fluids. Patients and government scientists began bombarding him with tips about other dangerous medical products on the market.

“It led me to think that there were an awful lot of problems that had been well documented, but no one had done anything about them,” Dr. Wolfe later told The Post. “It seemed more interesting to me to try to do these things than to do research.”

He founded the Health Research Group with Nader in 1971.

In 1980, he self-published “Worst Pills, Best Pills: A Consumer’s Guide to Avoiding Drug-Induced Death or Illness.” It has sold millions of copies and is now distributed by a division of Simon & Schuster. A decade later, the MacArthur Foundation awarded him a “genius” fellowship and $350,000.

“People like Sid can really be a pain in the neck at times,” Edwards, the onetime FDA commissioner, told The Post in 1989. “You have to take your hat off to somebody who has devoted his career to what he’s devoted it to. There are certainly careers that are more fashionable, more lucrative, where you get a lot more kudos.”

Fashionable and lucrative were, indeed, words seldom uttered in the same sentence about Dr. Wolfe, who for years never made more than $50,000 annually and whose wardrobe tended toward rumpled dress shirts and Harris tweed jackets.

Dr. Wolfe’s first marriage, to Ava Albert, ended in divorce. In 1978, he married Goldberg, a clinical psychologist and artist.

In addition to his wife, of Washington, survivors include four children from his first marriage, Hannah Wolfe and Rachel Wolfe, both of Manhattan, Leah Wolfe of College Park, Md., and Sarah Wolfe of Salt Lake City; two stepsons, Nadav Savio of Oakland, Calif., and Stefan Savio of Pittsfield, Mass.; a sister; and five grandchildren.

Friends and family members often asked Dr. Wolfe for health advice. Many of his colleagues were big on vitamins. Not Dr. Wolfe.

“A lot of public interest people take vitamins, apparently,” he told The Post in 1978. “I tell them that they’re chemicals, that they’re made by the big drug companies just like the stuff they’re fighting against, but they don’t listen.”